Somalia, like much of Africa, carries a long and painful memory of colonial manipulation. The strategies of divide and rule employed by foreign powers are not abstract concepts buried in history books; they are lived experiences passed down through generations. From the partitioning of territories to the distortion of indigenous governance systems, Africans have seen how external actors exploit internal divisions to serve their own strategic interests.

Colonial powers did not arrive in Africa as neutral partners. They disrupted established systems of law, governance, culture and religion, often by identifying local actors willing to pursue short-term gains in exchange for access to land and authority. These arrangements, presented as agreements or protectorates, eventually became tools of dispossession. Borders were drawn not according to social cohesion or historical continuity, but to satisfy imperial interests, often dividing communities and sowing long-lasting instability.

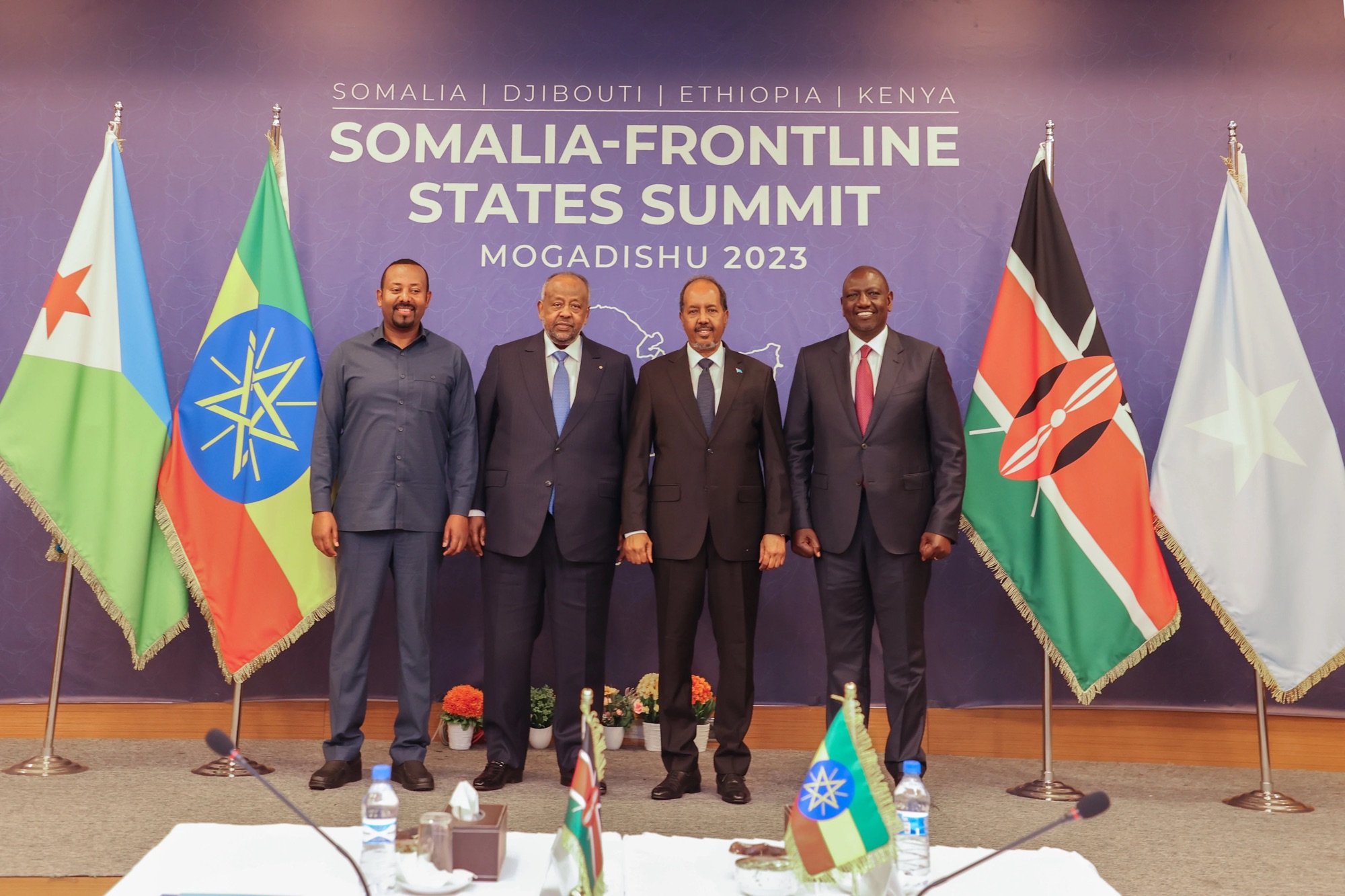

It is against this historical backdrop that current developments in the Horn of Africa must be understood. In 2026, it is deeply concerning to see Israel appearing to pursue a strategy that disregards international law and Somalia’s sovereignty, seemingly driven by strategic interests linked to access to the Red Sea. Such manoeuvres echo a familiar and discredited playbook — one that underestimates local realities and overestimates external leverage.

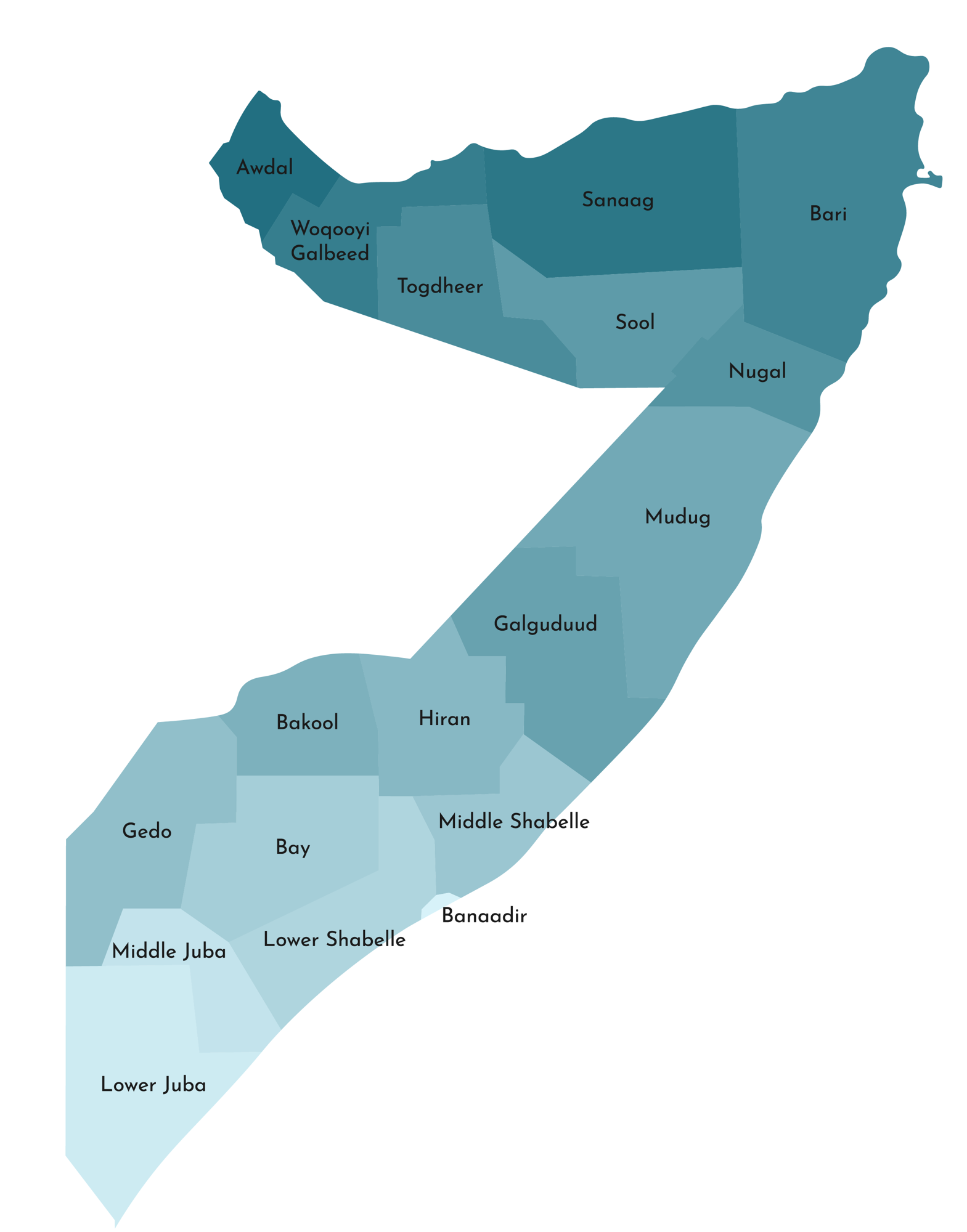

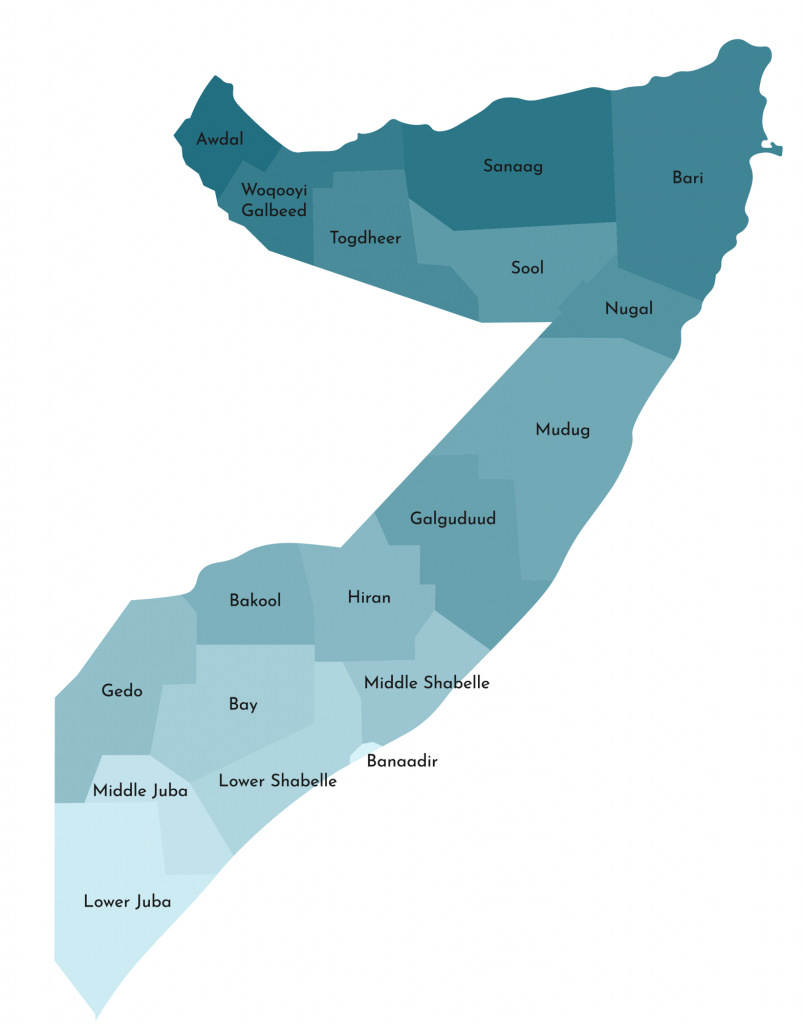

The most vulnerable entry point for this ambition appears to be the self-declared Somaliland administration. Yet this calculation rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of Somalia and the political realities of the northern regions. Somaliland is not a homogenous entity, nor does it represent a unified will to secede from Somalia.

The north-eastern regions are already functioning federal member states within the Federal Republic of Somalia, participating in nationally recognised governance structures. Meanwhile, regions such as Awdal have consistently rejected secessionist ambitions. The people of Awdal are deeply committed to Somali unity and have long opposed being subsumed under a project driven largely by clan-based dominance emanating from Hargeisa.

Under the current Somaliland administration, many non-Isaaq communities have faced systemic marginalisation, limited political representation and injustices that shape every aspect of daily life. Power remains concentrated among a narrow elite, leaving large sections of the population without a meaningful voice in decisions that affect their future. To portray this administration as a legitimate vehicle for statehood or international agreements is to ignore these internal fractures.

Somalia remains a sovereign state, recognised by the international community. Any attempt to dismantle its territorial integrity will fail, not merely because of legal constraints, but because the Somali people themselves will not allow it. National identity in Somalia runs deeper than temporary political arrangements or external inducements.

Narratives suggesting that Somalia is an open arena for geopolitical experimentation are misleading and dangerous. Whatever Israel’s intentions may be, any attempt to establish a physical or strategic foothold in Somalia through divisive means would represent a serious miscalculation. History has shown, time and again, that such ventures often end not in success but in enduring lessons — lessons later taught in classrooms as warnings against arrogance and historical amnesia.

Somalia today is undeniably fragile, grappling with complex governance, security and development challenges. Yet fragility should not be mistaken for absence. The Somali state is alive, and more importantly, it is protected by the vigilance of its sons and daughters — at home and across the diaspora — who remain steadfast in defending its unity, sovereignty and dignity.

Divide and rule failed in the past. It will fail again in Somalia