Somalia’s relations with Ethiopia and Kenya are often framed in diplomatic language that emphasises “regional cooperation” and “African brotherhood.” Yet history, and current realities, tell a far more troubling story—one that Somalia can no longer afford to ignore.

Both Ethiopia and Kenya share a dark and unresolved past with Somalia. During the colonial era, large Somali-inhabited territories were detached from Somalia and incorporated into Ethiopia and Kenya by the British, largely as punishment for Somali resistance against colonial rule led by the anti-imperialist freedom fighter Sayid Mohamed Abdille Hassan. These decisions planted the seeds of conflict that continue to destabilise the Horn of Africa.

Following independence, the Somali Republic sought to reunify its divided people. Under the military government, Somalia pursued the recovery of its lost territories, culminating in the 1977–78 war with Ethiopia. Somalia came close to defeating the Derg regime and advancing towards Addis Ababa, only to be stopped when Western and allied powers intervened to rescue Ethiopia. The consequences of that intervention are still being felt today.

In Kenya, Somali grievances were met not with dialogue but with repression. The Wagalla massacre of the 1980s—one of the darkest chapters in Kenya’s post-independence history—remains a symbol of the systematic marginalisation and collective punishment of ethnic Somalis. Accountability has been limited, and the underlying issues unresolved.

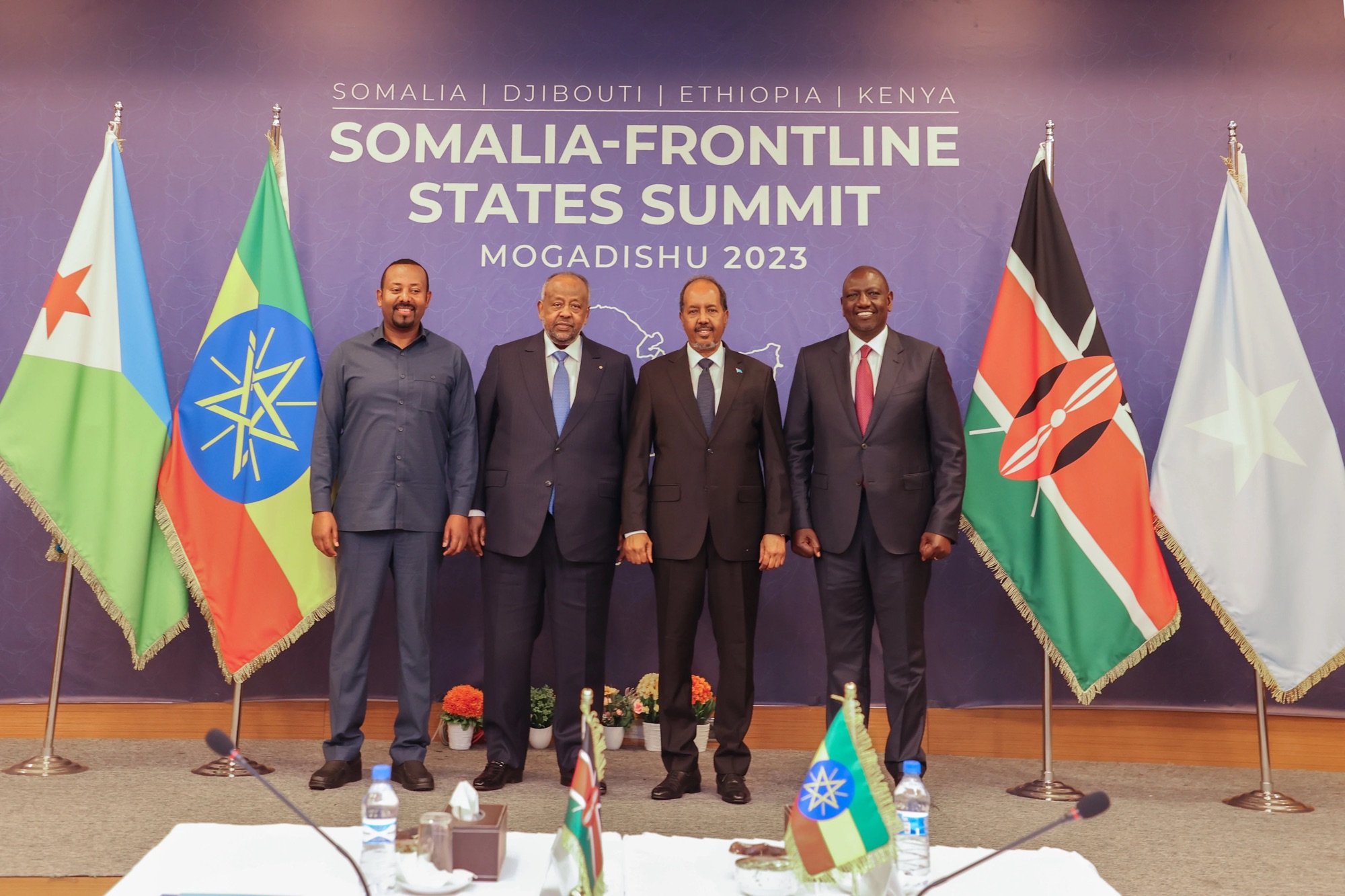

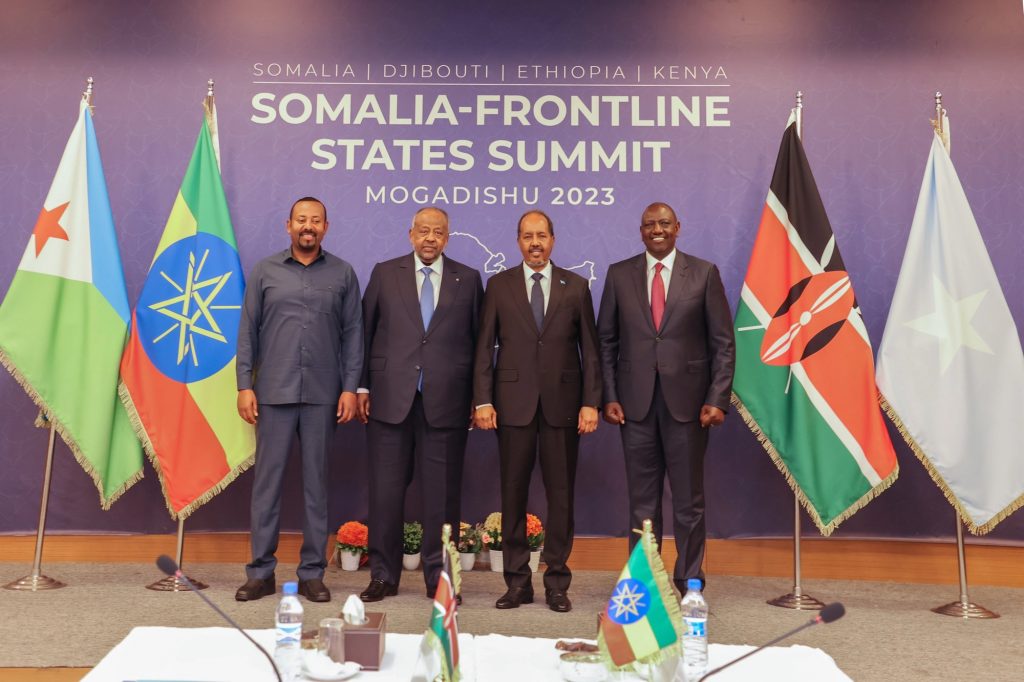

Since the collapse of the Somali state in 1991, both Ethiopia and Kenya have played an outsized and deeply problematic role in Somalia’s internal affairs. Under the banner of peacekeeping, both countries entered Somalia militarily without invitation and were later absorbed into the African Union Mission (AMISOM), and subsequently its successor missions. Their presence has been legitimised internationally, but their conduct on the ground raises serious questions.

Rather than acting as neutral stabilisers, Ethiopia and Kenya have often pursued narrow national interests—collecting international funds, shaping local politics, and supporting factions aligned with their strategic agendas. Any genuine gains made by Somalis towards stability and sovereignty have frequently been undermined by this interference.

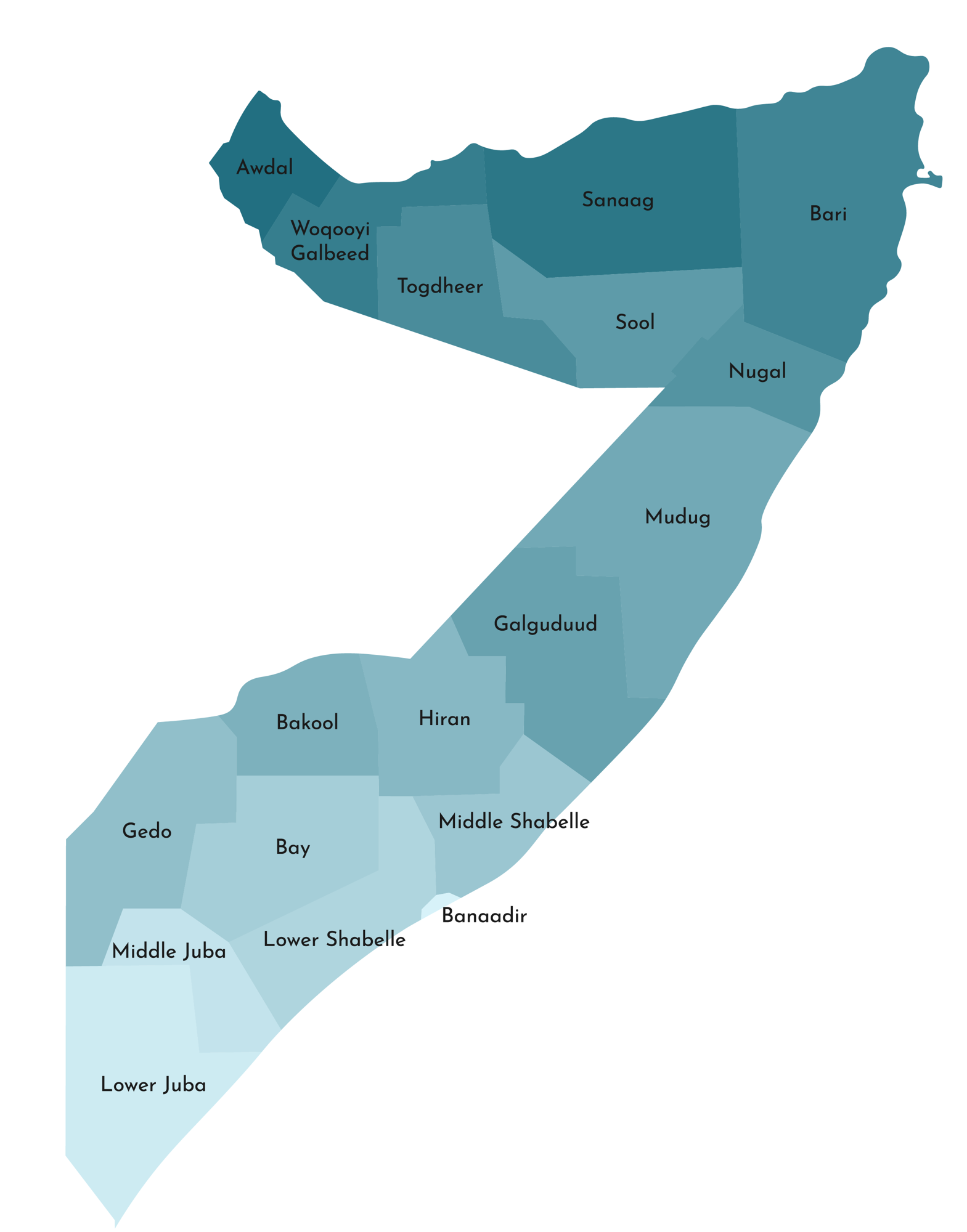

Both countries have also sought to exploit Somalia’s prolonged fragility. Attempts to encroach upon Somali maritime resources and land, as well as political manoeuvres aimed at weakening Somali unity, have been persistent features of their engagement. Support—direct or indirect—for fragmenting Somalia stands in stark contrast to their own domestic policies.

Ironically, neither Ethiopia nor Kenya tolerates similar secessionist aspirations within their borders. Kenya has responded harshly to coastal communities calling for autonomy, while Ethiopia has been accused of committing serious human rights abuses in Tigray, Oromia, and the Somali Region against groups seeking greater self-determination. This double standard exposes the hollowness of their rhetoric on Somali federalism and “local governance.”

More recently, their silence in the face of external interventions and geopolitical manoeuvring involving Somaliland raises further concerns. Such omissions are unlikely to be coincidental. They reflect a broader pattern of regional opportunism that treats Somalia not as a sovereign equal, but as a geopolitical playground.

Somalia’s leadership must therefore reassess its assumptions. Vigilance is no longer optional. A clear contingency strategy is needed to manage the behaviour of neighbouring states whose actions consistently contradict claims of friendship and solidarity.

One concrete step would be to push for the removal of Ethiopia and Kenya from UN-authorised peace missions in Somalia. Peacekeeping forces should come from genuinely neutral states, not neighbours with long-standing territorial, political, and security interests. Limiting their involvement would reduce interference in Somalia’s internal affairs and restore a measure of Somali agency over its own future.

Somalia has paid a heavy price for ignoring uncomfortable truths. The time has come to confront them—calmly, strategically, and without illusion.