The Finnish government’s decision to suspend development cooperation with Somalia while demanding the return of Somali migrants has sparked debate about Europe’s approach to migration, human rights, and the use of development aid as a political tool.

At a recent meeting of Finnish ambassadors, Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Ville Tavio (Finns Party) confirmed that aid to Somalia will remain suspended. He linked this directly to the Somali government’s reluctance to accept citizens ordered to leave Finland, many of whom are facing deportation. Critics, however, argue that such policies expose the failure of European countries—including Finland—to provide fair opportunities for immigrants, while placing fragile states like Somalia in even more difficult positions.

For decades, Somali immigrants have sought safety and opportunity in Europe, yet many face systemic barriers to integration. Community leaders argue that Somalis encounter disproportionate hurdles in obtaining residence permits, work opportunities, and an environment in which they can thrive. Instead of addressing these structural challenges, governments are increasingly resorting to deportations.

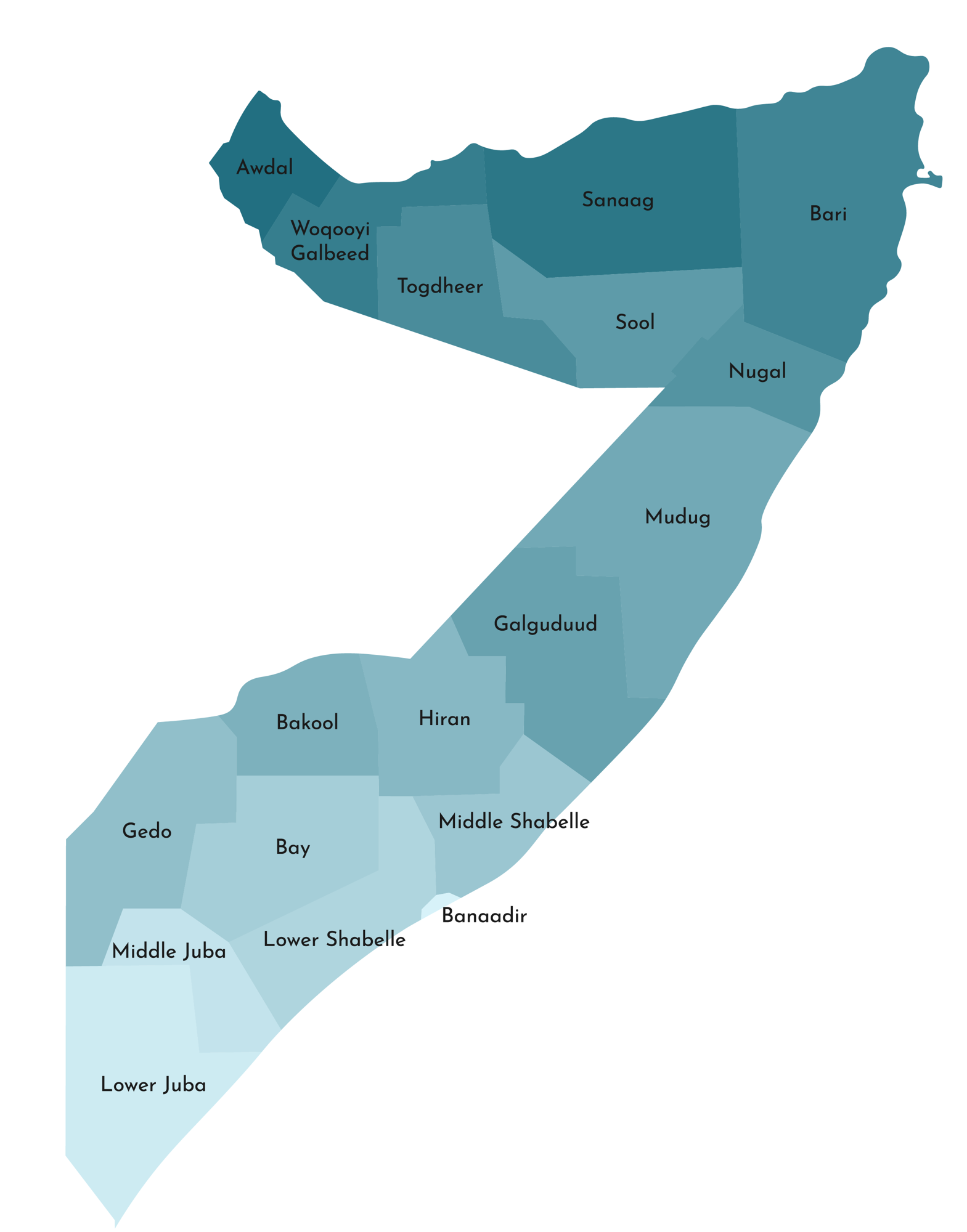

Human rights defenders warn that returning individuals against their will, particularly to a country struggling with instability, amounts to a violation of international law. Somalia continues to grapple with insecurity, weak institutions, and humanitarian crises, making forced returns deeply problematic. The risk is that vulnerable individuals—regardless of their past circumstances—are being sent to a place where their safety and future cannot be guaranteed.

Moreover, Finland’s approach raises questions about the use of development aid as leverage. By suspending €8–9 million in annual support earmarked for Somali women and girls, critics say Finland is effectively using aid to pressure Somalia into accepting deportees. If many of those deported are indeed convicted criminals, as officials claim, this practice could destabilize Somalia further by transferring Europe’s problems into a fragile state—rather than supporting constructive solutions that benefit both sides.

Observers also point out that linking aid to deportations sets a troubling precedent for international cooperation. Development aid is meant to uplift vulnerable populations, not serve as a bargaining chip in migration disputes. Somali activists and European human rights groups alike argue that this policy risks undermining trust and creating deeper divides between Africa and Europe.

With an estimated 20,000 Somalis living in Finland—most of them long-term residents or second-generation citizens—the Somali community has become an integral part of Finnish society. Many fear that current political rhetoric unfairly paints all Somalis through the lens of crime and deportation, rather than acknowledging their contributions.

The debate now extends beyond Finland. Across Europe, governments are under pressure from far-right movements to tighten migration policies, often at the expense of human rights. For Somalia, the stakes are high: accepting large numbers of returnees under such circumstances risks social strain, while rejecting them invites aid suspensions and political isolation.

In the words of one Somali community leader in Helsinki: “If Europe truly values human rights, it must create opportunities for immigrants to succeed, not punish them with deportation or use aid to destabilize our homeland.”