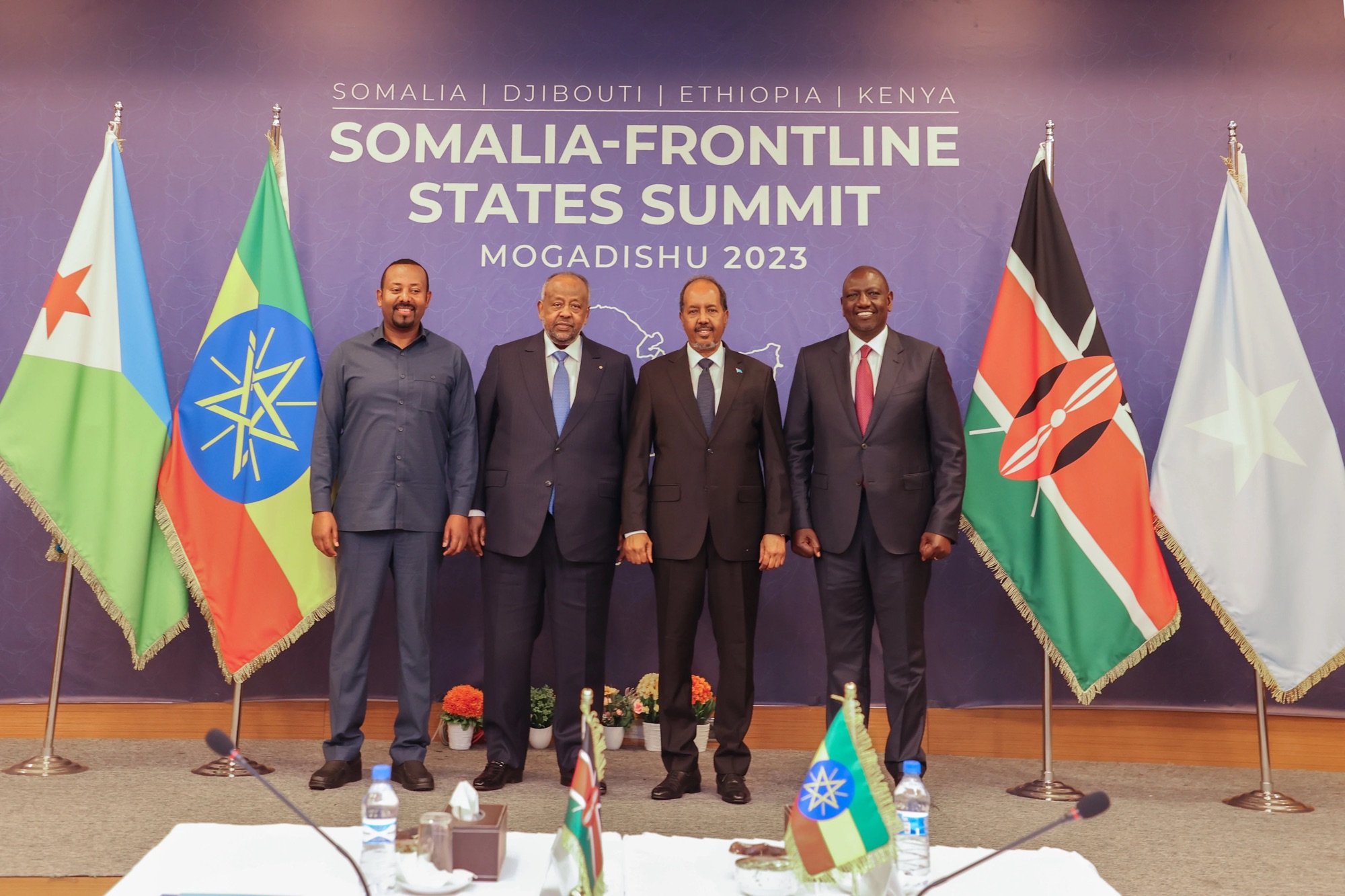

Somalia has long grappled with a complex and contentious electoral process. For the past five presidential elections, the country has adhered to an indirect electoral model. Tribal elders, selected from various clans, have played a pivotal role in electing members of parliament and the senate. Over time, the number of elders involved in these elections has grown, creating a sprawling network of decision-makers. However, the most recent election underscored the deep flaws in this system. The process handed significant power to state leaders, who oversaw the election of MPs, leading to widespread corruption and the election of unqualified individuals. Once in parliament, these MPs further tarnished the democratic process by engaging in blatant vote-buying, culminating in the election of President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud.

Now in office, President Hassan has vowed to end the cycle of indirect elections and usher in a new era of direct democracy. His vision includes empowering the Somali people to cast their votes directly, through a unified electoral commission overseeing both federal and state-level elections. In this proposed framework, federal states would conduct free and fair elections, enabling citizens to elect governors, members of parliament, senators, and other leaders. While the vision is ambitious, the viability of implementing direct elections by 2026 is fraught with significant challenges.

The Challenges of Transitioning to Direct Elections

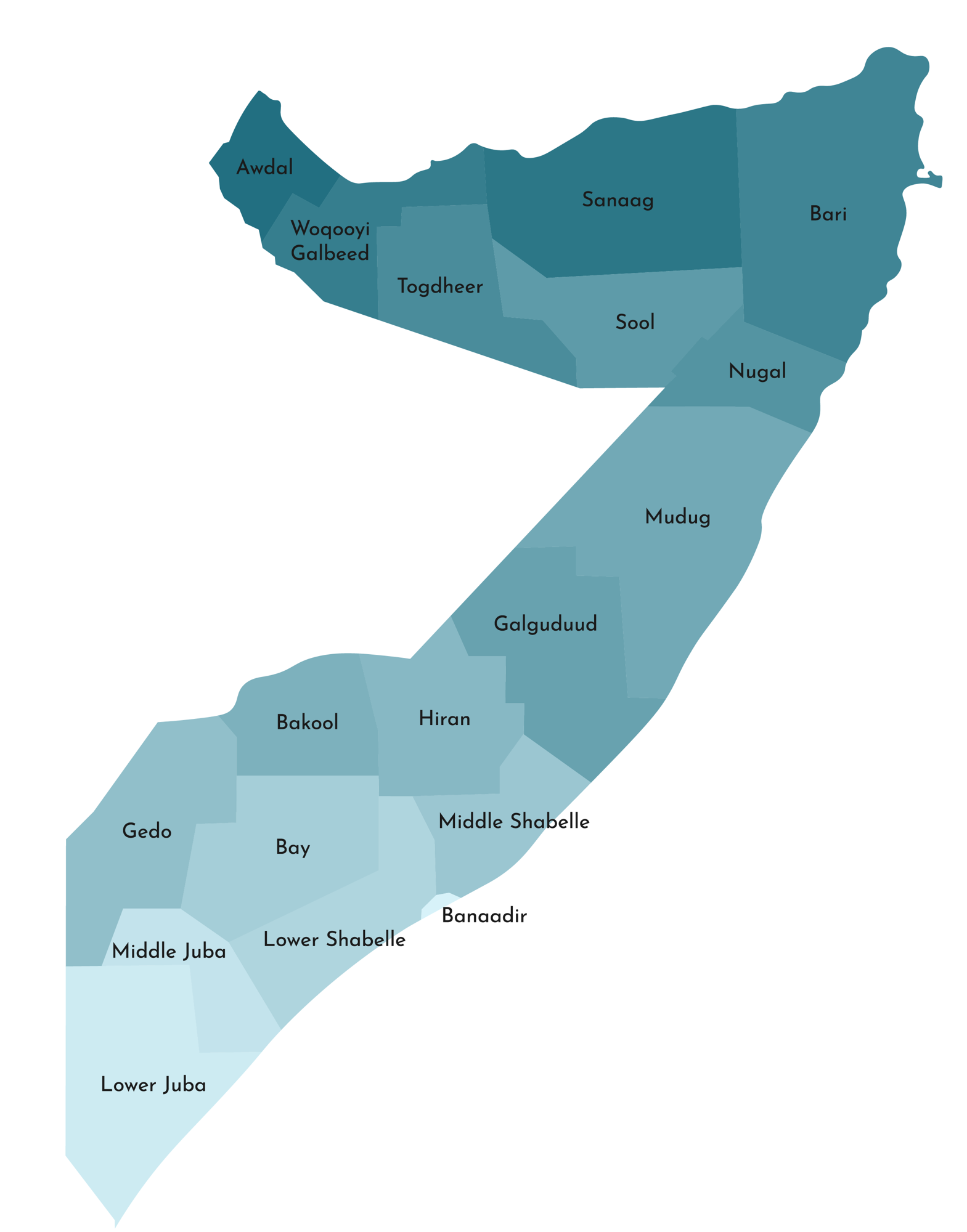

One of the foremost obstacles is Somalia’s ongoing security crisis. Large swathes of the country remain under the control of Al-Shabaab, an extremist group that has demonstrated its capacity to disrupt any attempts at stability. Conducting elections in these regions is simply not feasible under current conditions. For a credible nationwide election, the federal government would need to reclaim and secure these areas—a herculean task that demands time, resources, and international support.

Further complicating the picture is the strained relationship between the federal government and several states. Somaliland, Puntland, and Jubaland, in particular, have contentious dynamics with President Hassan’s administration. These tensions have led to political standoffs, making it unlikely that elections can be conducted in these regions without significant negotiations and compromises. In Jubaland’s Gedo region, for instance, clashes between Somali and Ethiopian forces have exacerbated instability, particularly in towns like Dolow. The Ethiopian army’s support for Jubaland’s state representatives only heightens the political complexity, creating barriers to establishing a unified electoral process.

A Race Against Time

With only 16 months remaining before the proposed 2026 elections, time is not on the government’s side. Establishing a unified electoral commission, resolving disputes with federal states, ensuring security, and educating citizens on the voting process are monumental tasks that require meticulous planning and execution. The absence of a cohesive agreement among stakeholders further hampers progress. Without consensus, any attempt to hold elections risks being labeled illegitimate, further fracturing the nation’s fragile unity.

Skepticism and Distrust

While President Hassan’s vision has garnered some support, skepticism abounds. Many Somalis are wary of his intentions, fearing that the push for direct elections may be a veiled strategy to extend his tenure or consolidate power. Trust in the government’s ability to deliver a fair and transparent process is at an all-time low, and overcoming this mistrust is crucial for the viability of any election.

The Path Forward

To make direct elections a reality, Somalia must address several critical issues:

- Security: Restoring security in Al-Shabaab-controlled areas is paramount. This requires a concerted effort by the Somali National Army, regional forces, and international allies to dismantle the group’s stronghold and create a safe environment for voters.

- Federal-State Relations: Building trust and cooperation between the federal government and states like Somaliland, Puntland, and Jubaland is essential. A collaborative approach that respects the autonomy of states while fostering unity is crucial for success.

- Electoral Infrastructure: Establishing a credible and independent electoral commission to oversee the process is a cornerstone of free and fair elections. This body must be empowered to operate without political interference, ensuring transparency at every level.

- Civic Education: Educating citizens about their voting rights and the importance of direct elections is vital. A robust awareness campaign can help combat voter apathy and ensure widespread participation.

- Time Management: Given the tight timeline, the government must prioritize tasks and allocate resources efficiently. Early wins in security and stakeholder engagement could build momentum and instill confidence in the process.

Conclusion: A Daunting Yet Necessary Endeavor

The viability of a national election in Somalia by 2026 hangs in the balance. While President Hassan’s vision of returning power to the people is laudable, the road ahead is fraught with challenges. Security concerns, political rivalries, logistical hurdles, and a lack of trust pose significant barriers to success. However, with strategic planning, international support, and a genuine commitment to reform, Somalia can begin to lay the foundation for a more democratic future.

The stakes are high. Failure to deliver on this promise could deepen the country’s political divisions and erode public trust even further. Conversely, a successful transition to direct elections could mark a turning point in Somalia’s history, setting the stage for a more inclusive and representative democracy. Whether 2026 becomes a milestone year or a missed opportunity will depend on the collective will of Somalia’s leaders and people to overcome the challenges that lie ahead.