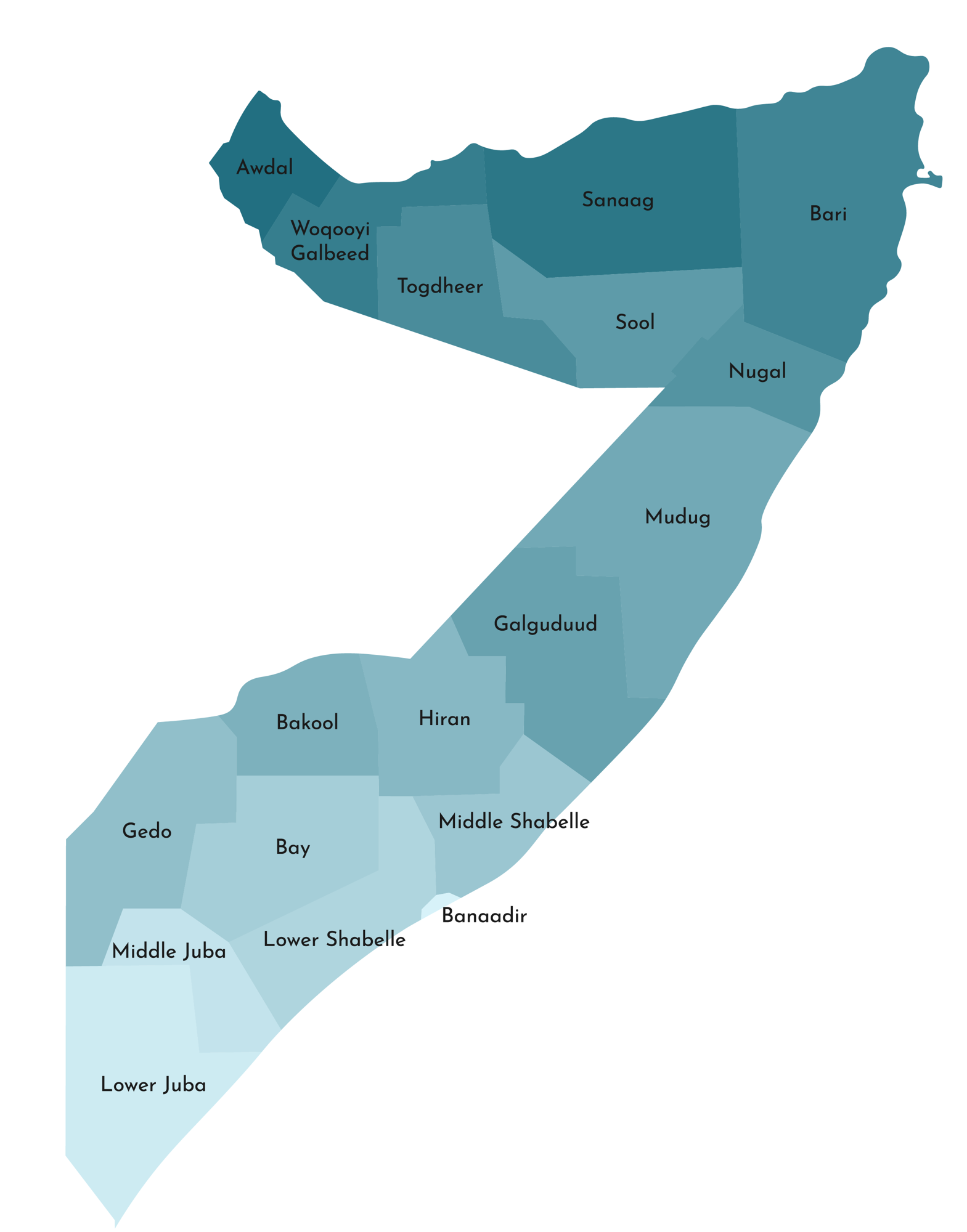

For more than three decades, Somaliland has presented itself to the world as a peaceful, unified, and consensual breakaway state. This narrative has found sympathy in some international circles, particularly when contrasted with Somalia’s long struggle with instability. Yet when the Somaliland project is examined beyond Hargeisa—through the experiences of regions such as Awdal and SSC-Khaatumo—a more troubling and complex picture emerges.

From Awdal’s perspective, the problem is not merely political disagreement; it is a fundamental question of consent, legitimacy, and the use of force.

Awdal’s Longstanding Call for Somali Unity

The people of Awdal have consistently rejected unilateral secession. This position is often mischaracterised as nostalgia for a failed state or opposition to accountability for past crimes. In reality, Awdal’s stance is rooted in a belief that Somalia’s collapse should be addressed through reform and federalism, not fragmentation imposed by one political centre.

Awdal has never denied the atrocities committed by the former Somali military regime in the 1980s. Those crimes were real and devastating. But historical injustice cannot justify new injustices, nor can it grant one group the authority to permanently decide the fate of others.

The Borama Violence of 1994: A Silenced History

In 1994, Borama—Awdal’s capital and a city known for scholarship and peace—became the site of violent repression. As Awdal resisted incorporation into Somaliland’s secessionist institutions, armed forces affiliated with Somaliland entered the city.

Civilians were killed, homes and businesses were targeted, and intimidation was used to suppress political dissent. This violence occurred after the fall of the Somali military regime, undermining claims that Somaliland’s use of force was purely defensive or reactive to past atrocities.

Unlike the well-documented crimes of the 1980s, the Borama massacre has received little international attention or investigation. For many in Awdal, this silence reinforced a painful lesson: some Somali lives are deemed more worthy of remembrance than others.

Laascaanood and the Collapse of the “Peaceful Somaliland” Image

Nearly three decades later, similar patterns emerged in Laascaanood, the capital of the SSC-Khaatumo regions. When local communities openly rejected Somaliland’s authority in 2022, the response was not dialogue but militarisation.

Independent reporting documented indiscriminate shelling of civilian neighbourhoods, the killing of children, destruction of hospitals and schools, and mass displacement. These actions raised serious allegations of violations of international humanitarian law.

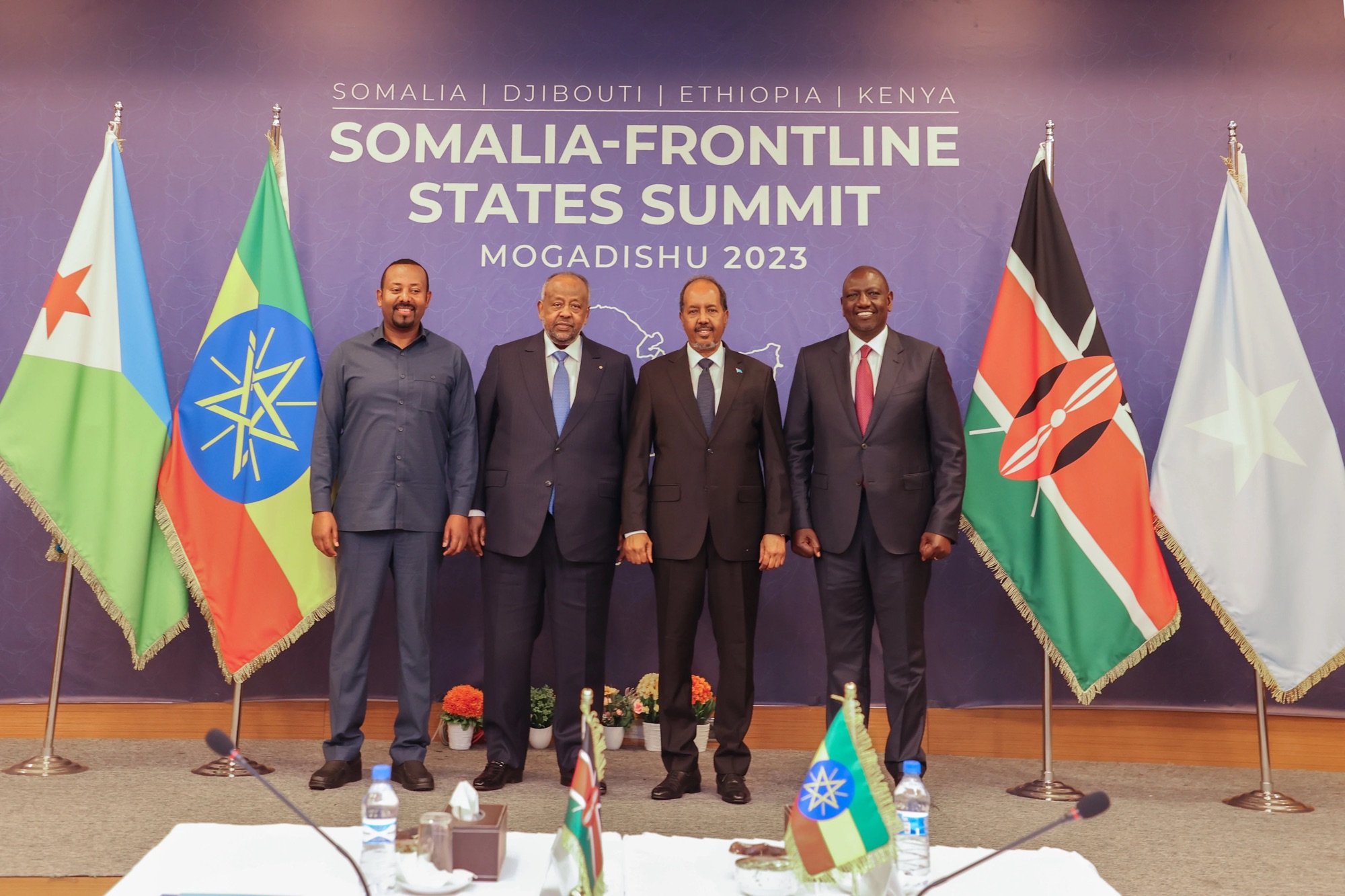

The outcome was decisive. SSC-Khaatumo forces expelled Somaliland troops, and in 2023 the region formally aligned itself with the Federal Government of Somalia. Mogadishu recognised SSC-Khaatumo as a federal administration, effectively removing a major territory from Somaliland’s control.

This moment shattered the claim that Somaliland’s authority rests on voluntary consent. Where people were able to assert their will, that authority collapsed.

Awdal and SSC-Khaatumo: Parallel Trajectories

Awdal today observes clear parallels with SSC-Khaatumo’s experience. Both regions rejected secession, both faced marginalisation, and both encountered coercion rather than accommodation. The difference is that Awdal continues to pursue its position through peaceful political mobilisation, determined to avoid the bloodshed witnessed elsewhere.

The growing support Awdal receives from Somalis across the country and the diaspora reflects a broader reality: Somali unity still commands deep moral and political support, particularly when framed within a federal system that respects local autonomy.

Rights for Hargeisa, But Limits to Secession

None of this is an argument against the rights of the people of Hargeisa. They are Somalis and deserve protection, dignity, equal citizenship, and full political participation. Their historical grievances must be acknowledged honestly and addressed meaningfully.

However, no community has the legal or moral right to divide Somalia unilaterally, engage foreign states in pursuit of recognition, or advance geopolitical agendas that undermine Somalia’s sovereignty. Such actions are illegal under international law and risk destabilising an already fragile region.

Unity does not mean denying diversity or silencing grievances. But sovereignty cannot be optional, nor can it be negotiated by force.

Conclusion: Consent, Not Coercion

Somaliland’s secession project is becoming increasingly impractical not because of external hostility, but because of its internal contradictions. A state cannot claim legitimacy while suppressing dissenting regions. It cannot invoke self-determination while denying that same right to others.

Borama in 1994 and Laascaanood in 2022–2023 are not isolated incidents; they are warnings. From Awdal’s perspective, the path forward lies not in deepening division, but in rebuilding Somalia through justice, accountability, and voluntary unity.

The choice facing Somalis today is not between unity and chaos, but between coercion and consent. History suggests only one of these leads to lasting peace.